The inner world of a design leader

# Navigating the identity shift from maker to multiplier

It's not a dream, it's a Tuesday

Have you ever had that dream? The one where you’re on stage, giving that once-in-a-lifetime TED Talk, the audience is engaged, lapping up every word, you’ve finally made it…. Then you look down, and time stops. For it's in that moment you realise you’ve got no trousers on. And in that split second of horror, you have to decide. Do you carry on and pretend that everything is normal? Do you acknowledge the wardrobe malfunction? Or do you just turn and run, and never, ever return to that place?

Well, for a design leader, that isn't a dream. It's a Tuesday.

Then you look down....

...and time stops...

It’s the feeling of imposter syndrome, and I can say with absolute certainty that it hits us all at some point. It’s that constant, nagging companion in a creative career, from the most junior designer to the most senior VP. And it often starts with a promotion. You’re brilliant at your job, so you’re given a new one. This is, of course, The Peter Principle in action: the idea that we are all eventually promoted to our level of incompetence. We’re given a new role based on being good at our old one, not on any proven aptitude for the one we’re about to do.

The physics are strangely different

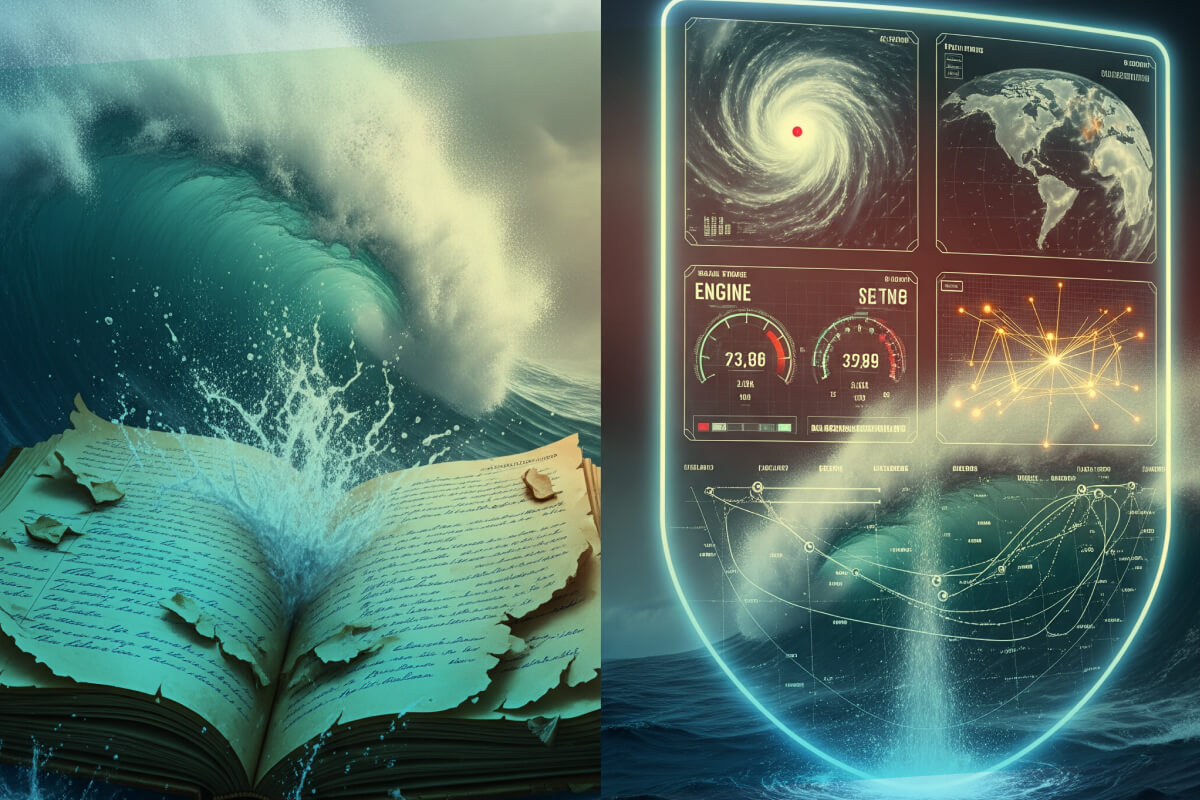

For designers, this is compounded by the jarring identity shift from being a Maker to a Multiplier. Suddenly, all the skills you've spent years honing to make you a brilliant designer feel... dulled. You’re in a new world now. The landscape is familiar, but the physics are strangely different. Your success is no longer measured by your own tangible output, but by the indirect, often invisible, impact you have on your team.

And so you find yourself living in two metaverses at once. You are a comrade in the trenches, deep in a Figma file trying to help unblock a project, and you are a general on the hill, trying to keep calm and see the whole war, ensuring the team's work aligns with a grand strategy. You become the team’s shock absorber, shielding them from the chaos of the wider business. And at the end of it all, you have very little tangible work to show for it.

The great thief of joy

And this whole psychological mess is then amplified by the great thief of joy, as Theodore Roosevelt called it: comparison. We scroll through our feeds, a curated museum of other leaders' victories, the successful product launch, the glowing team offsite photo. We don’t see the messy reality, the late-night anxieties, or the failed experiments. We only see the highlight reel, and it becomes a brutal, and entirely unfair, measuring stick against which our own chaotic, "invisible" work can feel profoundly inadequate.

"Your job is no longer to design the product. It is to design the team."

The hardest thing you'll ever design

For a long time, stepping into leading other people felt like a profound loss. It felt like I wasn't a "real" designer anymore. But the only way through this identity crisis is to learn to see your work through a new lens. It requires you to consciously redefine what "success" looks like. Success is no longer a perfect Figma file. It’s the moment a junior designer, who was terrified three months ago, confidently defends their work in a tough critique. It’s the quiet thank-you message from an engineer because you helped them untangle a complex problem. It’s seeing your team ship something brilliant while you were on holiday.

Your job is no longer to design the product. It is to design the team.

It's a new kind of satisfaction. It's quieter, less direct, but ultimately, I think, more profound. It's the hardest thing I've ever had to design. And it's the only thing that really matters.