On stopping the 'pub brawl' to save the product

# A case study in redesigning a team's process to solve a complex product challenge.

At a glance

The challenge

My design team was halved from 12 to 6, leaving the strategic onRADAR product stream without a designer. I stepped in as Lead Designer (Player-Coach) to salvage the failing feature. I found it paralysed by a chaotic, "drive-by" feedback culture that masked the core product flaw: 'Alerts' and 'Tasks' were a confusing, tangled mess sharing the same code.

My role

As Lead Designer/Head of Design (Player-Coach), I partnered with Product and Engineering to diagnose the root cause. I was responsible for fixing the team process, defining the product strategy, and executing the hands-on UX/UI design.

The process

I replaced the chaotic feedback loop with a structured 'silent critique' process. This new framework created a calm, focused environment, allowing us to collaboratively untangle the core product logic and define clear, separate user workflows.

The impact

The new critique process eliminated noise, reduced cross-functional friction, and allowed the team to move from paralysis to delivery. We successfully salvaged the product by separating it into two distinct, logical workflows ('Alerts' and 'Tasks'), creating a coherent user experience and a scalable model for remote, cross-team collaboration.

|

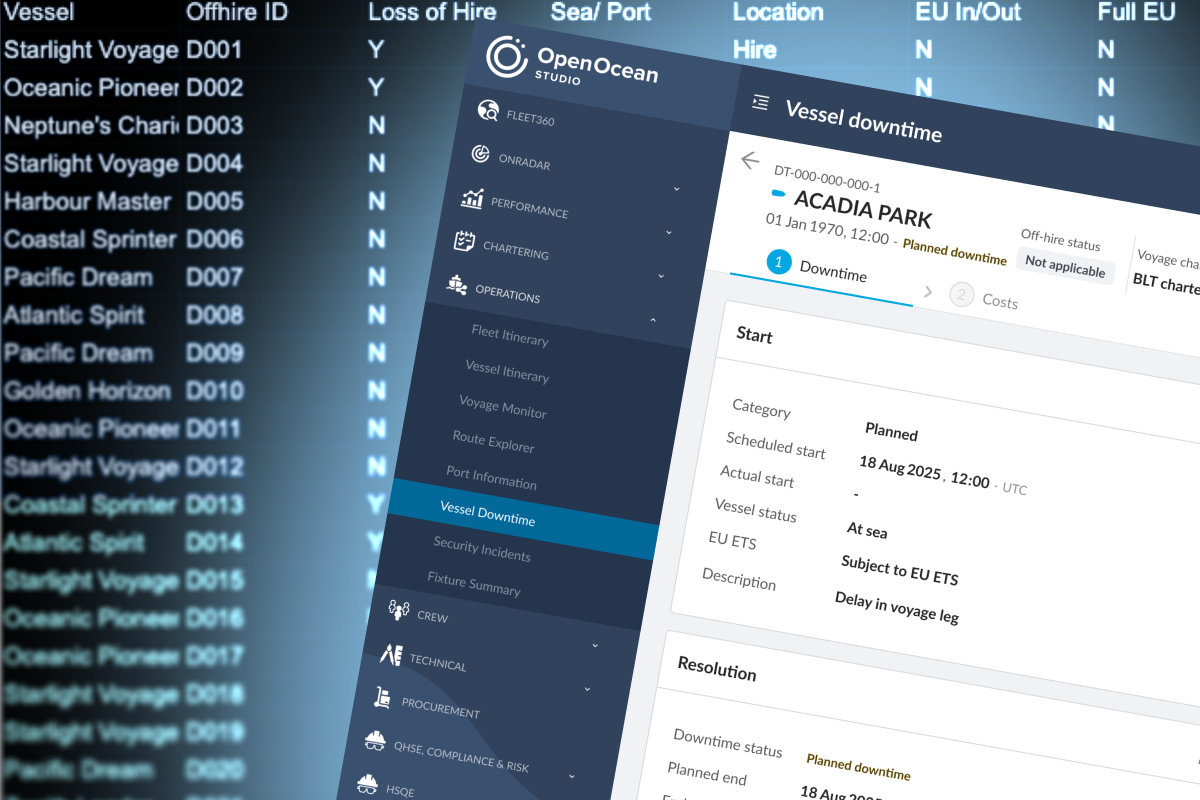

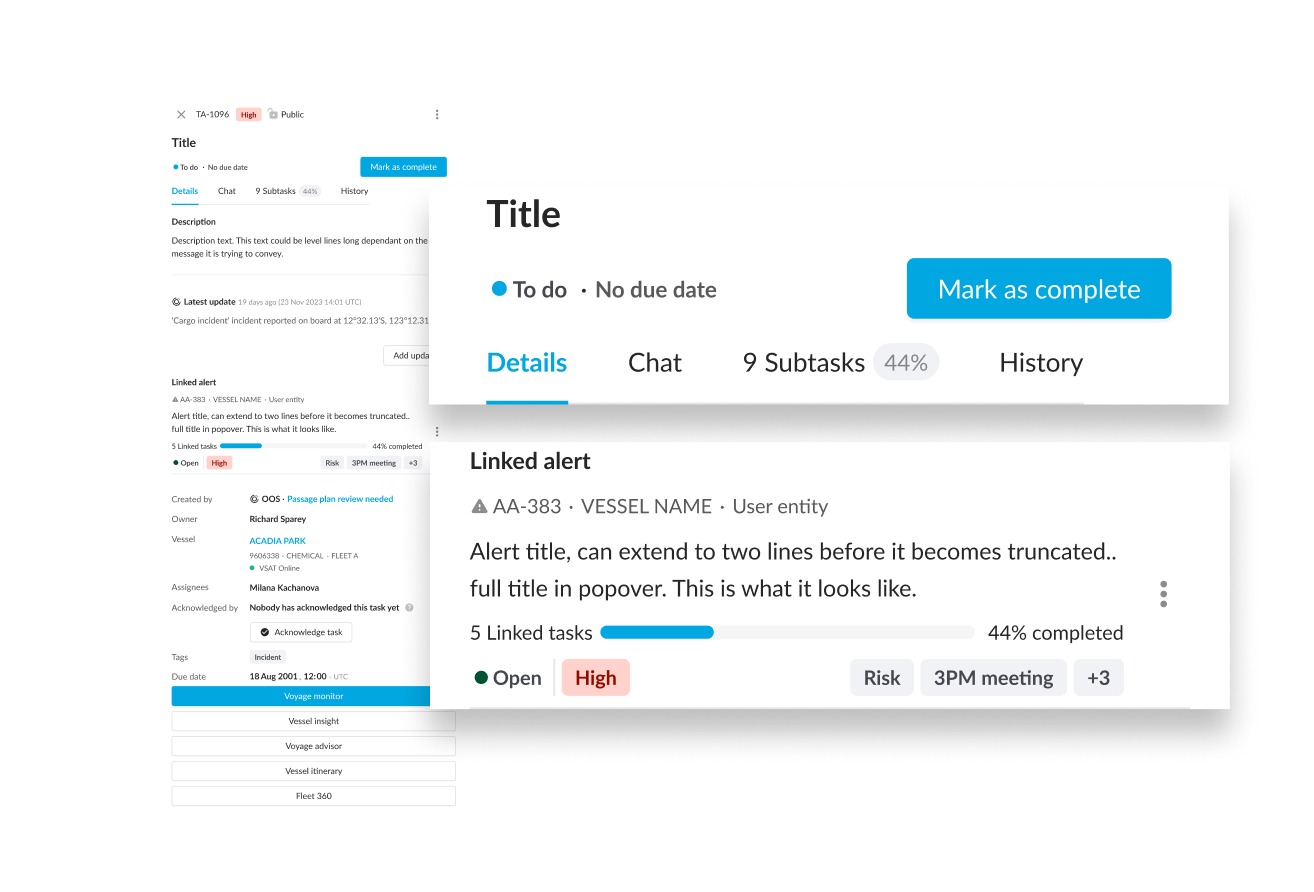

![A screenshot of the FigJam board used for the silent critique[cite: 569]. [cite_start]On the left is the prototype under review; on the right is the structured board where designers, engineers, and PMs added written feedback, creating a "calm, structured conversation](/application/files/6817/6113/8011/Critique_process.jpg)

Image: This is the engine room. On the left, the prototype being scrutinised. On the right, the FigJam board where we replaced a riot in a phone box with a calm, structured conversation. It's not glamorous, but this is what it takes to get a fully remote team of designers, engineers, and product managers all pointing in the same direction. It's the digital equivalent of a proper, grown-up meeting.

The challenge: Inheriting a fire

The player-coach nightmare

When I joined the onRADAR product team, I wasn't just given a project; I was handed a fire on three different fronts. At the heart of it all was the onRADAR alerts and tasks feature, a cornerstone of the entire OpenOcean Studio. But this cornerstone was connected to a chaotic soup of other parts: a rules engine, a mobile app for seafarers, and another for the shore-based team. This wasn't one busy team; it was several teams that I, as the designer, sat across. To make matters worse, I was also juggling a separate project for another team and my duties as the Design lead for the entire company. It was the classic "player-coach" nightmare.

A system of glorious chaos

And the project itself reflected this chaos. The "linked alert and task" project was a perfect example. Feedback was a chaotic spray of drive-by opinions in Figma, Slack, and a dozen conflicting Jira tickets. The design was already happening, just without a designer in the room. It became brutally clear that I couldn't even begin to untangle the actual product mess until I first fixed the way the team was talking to each other. It was like trying to perform open-heart surgery in the middle of a pub brawl.

|

|

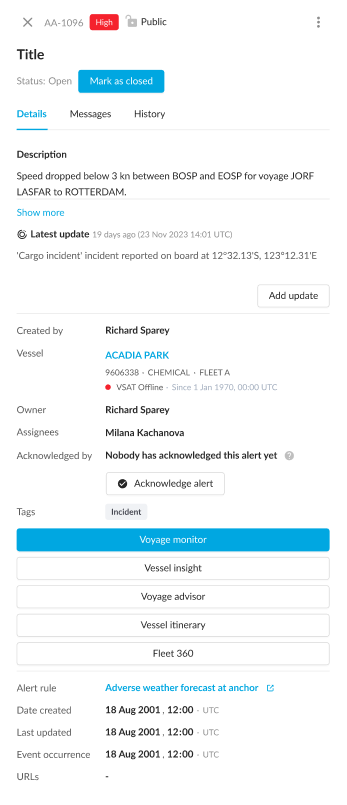

Image: And here we have it. The starting point. On the left, a drawer for a high-priority 'Alert'; on the right, a near-identical one for a 'Task'. They're practically twins.

And that was the entire problem, right there on. These two forms were for completely different jobs, yet they were, to all intents and purposes, the same. All because of our eagerness to save time by sharing code. The brief was to 'link' them, but the platform couldn't even distinguish between them.

It's like looking at a surgeon's scalpel and a butcher's cleaver and saying, 'Well, they're both for cutting, aren't they?'

The intervention: Architecting a moment of calm

The diagnosis

So, there you have it. A product tied in knots, a team pulling in three different directions, and a feedback process that resembled a riot in a phone box. Luckily, this wasn't my first rodeo. I had already spent months forging a brutally efficient critique process with the central design team. We had a system that worked. A system that replaced shouting with thinking.

The low-stakes experiment

But you can't just march into a new, cross-functional team and announce you're changing the laws of physics. They'll just look at you like you're mad. Instead, I made them a simple offer. In the next meeting, I said, "Look, the way we're doing this is clearly bonkers. It's not working for any of us. I have an idea I've seen work before. It has a few simple rules.

First, you share a link to the work a full day before the meeting. This gives everyone proper time to think. Then, when we meet, the designer gets the floor first to explain the problem and where they need help. Only then do we do the most important thing. We all shut up. I set a ten-minute timer, and everyone just writes their thoughts. Let's just try it once. If it's rubbish, we'll never speak of it again." Because the existing chaos was so obviously painful for everyone, they agreed.

The payoff: Untangling the product mess

The scalpel and the cleaver

So, we had our new process. Our first patient was the "linked alerts and tasks" project. The root of the problem was a classic piece of tangled, compromised logic. 'Alerts' and 'Tasks' are for completely different jobs. An 'Alert' is a high-priority alarm for an operator. A 'Task' is a lower-priority to-do item for an analyst. But inside the desktop app, they were both being built from the same, tangled mess of shared source code. It was like trying to forge a surgeon's scalpel and a butcher's cleaver from the exact same piece of steel. They're both designed to cut, but one is for delicate, life-saving precision, and the other is for smashing through bone. If you build them the same way, you end up with a tool that's clumsy in the operating theatre and useless in the abattoir.

The moment the penny dropped

In the old world of chaotic feedback, this crucial fact was always lost in the noise. But in the first session of our new, silent critique, the truth came out with brutal clarity. For the first time, we could have a grown-up, evidence-based conversation about the real problem. The silent, written format had given the engineers a platform to state a hard, technical truth without being shouted down.

A fork in the road

The solution, once we'd cleared away the noise, was obvious. We needed to architect a separation. We worked together to define one clear set of rules for the 'Alerts' workflow and another, distinct set for the 'Tasks' workflow. The feature was no longer a confusing mess. It was two distinct, logical workflows, born from a single, sane conversation.

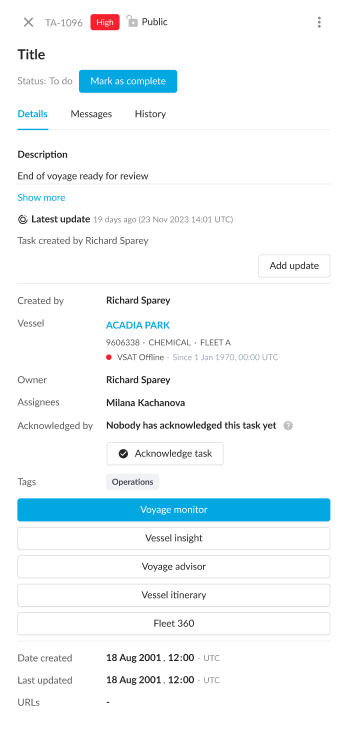

The small details that make all the difference.

Image: This isn't just a prettier panel. This is what happens when you finally bring some order to the asylum. Before I intervened, 'tags' and 'badges' were a complete mess, used by different teams for a dozen different reasons.

So, I created a simple rulebook: a clear set of guidelines for what a 'Status tag', a 'Category tag', and a 'Special tag' actually are.

The result is small, but significant. The status now gets a proper, colour-coded dot, a 'Status tag' that means the same thing here as it does everywhere else. We put the due date in the header where you can't miss it. Even the linked alert speaks the same, consistent language. It's the slow, painful, and deeply satisfying work of replacing a mess with a system.

The outcome: A smarter team, a better product

A cultural revolution

That first session wasn't a one-off success; it was a revolution. We immediately binned the old, chaotic ways of working and made the silent critique the mandatory, official process for the onRADAR team. The impact was profound: it killed the "drive-by" opinion, empowered engineers to contribute to the 'why', and eliminated the "design-before-the-designer" problem. We were simply faster.

From politician to designer

And for me, as the player-coach in the middle of this storm? It was a game-changer. I went from deciphering a Jira ticket full of conflicting instructions to leaving a meeting with a crystal-clear list of what needed to be done. The problem became a shared mission. It meant I could stop being a glorified politician and actually do my job.

A new weapon for remote collaboration

But the impact wasn't just limited to our team. The new process became a weapon for tackling the nightmare of cross-team dependencies, a problem made ten times harder in a fully remote company. Take the "adding a bank account" flow for the Seafarer App. In the old world, trying to coordinate two distributed teams would have been a logistical catastrophe of endless emails and conflicting Slack threads. Instead, I got everyone—the PMs, designers, and technical people from both teams—into a single virtual room on a FigJam board.rown-up conversation

Video: "The process in action: the silent critique for the cross-team 'add bank account' feature, showing the user flow, UI, and written feedback from both teams all on one board."