On dragging gym equipment into the 21st century, kicking & screaming

# The challenge of architecting a company's first smart, connected fitness platform.

At a glance

The challenge

I had already designed the company's foundational 'Smart Centre' gym system and its accompanying smartcard console. The new challenge was a "digital arms race": competitors' touchscreens were disqualifying us from critical government tenders. We had to pivot, and I was tasked with architecting the company's new digital future, starting with a connected touchscreen console.

My role

Senior UI/UX Designer, my role blended product management with design execution. I was responsible for establishing the UX discipline, defining all product strategy, and executing the hands-on UI/UX design, while partnering with external software suppliers and manufacturing partners to deliver the entire digital ecosystem.

The challenge

I architected the keystone Android touchscreen console, starting from paper prototypes and translating the vision into a 100-page manufacturing specification. I personally managed its refinement with engineers in Taiwan. This console became the gateway to a full cloud platform, a new mobile app, and a seamless NFC wristband, replacing the old system.

The impact

I masterminded the company's entire digital transformation. The new connected platform was a major commercial success, immediately unlocking the premium government and private tenders the company was previously locked out of. This ecosystem replaced the outdated smart card system, unified the member journey, and became the central pillar of the company's long-term strategy.

|

The strategic challenge: A digital arms race in a world of government tenders

In the world of commercial fitness equipment, you don't just sell to a gym; you win a war. A large chunk of the business is built on a brutal system of bids and government tenders. And the hard truth is that these tenders are often written with a winner already in mind. If a competitor has a fancy new touch screen on their treadmill, and you don't, you're not even allowed to turn up for the fight. You are disqualified before you've even started.

A good idea left behind

Image: "This console from the mid 2000's was a proper piece of work, and I should know, because I was responsible for most of it. From its non-touch interface, to the textured membrane with its physical buttons. That little smart card? Yes, that was one of mine too, from the original SmartCentre system this whole platform replaced. I’ve been wrestling with this problem for a while. And to cap it all off, I even took and retouched this photograph. Don't ask. Marketing department. It was a long day."

And in the mid-2010s, that's exactly what was happening. The technology was moving on. You could see it at the big trade shows: smaller, hungrier firms were experimenting with the newly affordable touch screen tech, and the big players like Technogym were already miles ahead.

At the same time, the entire idea of what a "gym" was, was changing. The days of a monolithic bank of TVs showing the same news channel were dead. People were getting used to on-demand, personal entertainment at home, and they were starting to expect the same on their cross-trainer. We were just before the Netflix wave hit properly, but you could see it coming.

Pulse Fitness was caught in the middle of this perfect storm. We had to respond to the tender-driven arms race and meet the shifting expectations of the public, or face becoming a relic. The challenge wasn't just to bolt a screen onto a treadmill; it was to define and deliver the company's entire digital future.

My influence & vision: Dragging a hardware company into the digital age

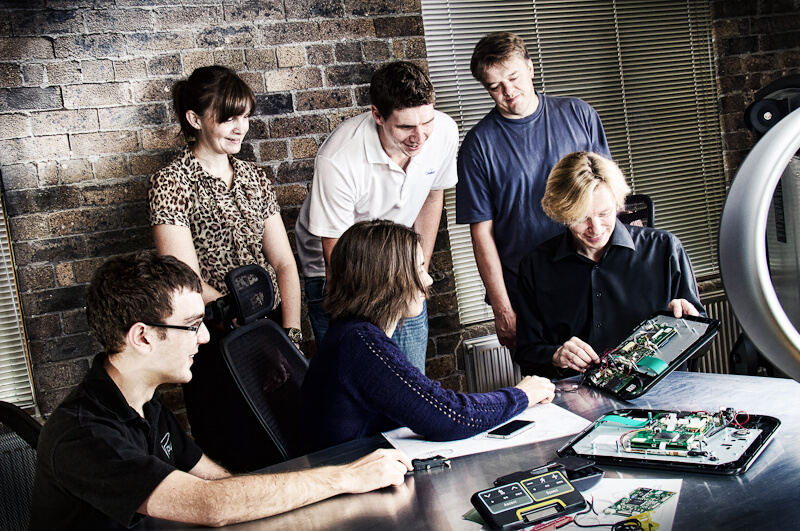

The team I was part of at Pulse was a lean, slightly eccentric, and dangerously effective group of specialists, most of whom were brilliant at making things you could kick. At the top, you had my mentor, Darren, a master of physical products—welded steel and injection mouldings—and the co-owner, Dave, whose focus was on getting those things built in the Far East.

The design studio was a proper workshop.

We had a couple of other industrial designers, a mechanical engineer, and downstairs, in a space filled with the glorious smell of metal and oil, Colin worked away building full-scale, working prototypes of the machines. We even had a dedicated tester, whose actual job it was to spend all day working out on the machines to try and break them.

Image: "This is the design team, just before I rejoined them to start work on the touchscreen console. You will notice I'm not in the picture. That’s because I'd been seconded to the marketing department, who'd decided my primary purpose in life was to take their brochure photography. For this shot, I reorganised the entire showroom and borrowed a massive sheet of stainless steel from a local fabricator to create our 'studio shot'. You don't get that sort of glamour at Apple."

Then there was the software outpost...

A small team, almost a separate entity, with a "product designer-manager" and an engineer focused on the Smart Centre gym management system—a product I had designed before they joined—and supporting the dozens of old embedded consoles on our other machines. And out in Taiwan, we had Tony, our genius embedded engineer who had moved out there with the production line.

This was a team that knew how to make things. My new job was to teach them how to make things you could tap.

When the decision was made to finally enter the touch screen arms race, I was already the being sent to the big European trade shows to see what was coming. Dave would pull into conversations with potential console partners. In fact, for the meeting with the supplier we eventually chose, Dave didn't even show up. So I found myself stepping up, fielding the initial calls, and starting the conversation that would define the company's next decade.

The initial plan was, of course, to do the simple thing: take all the brilliant fitness programs from Tony's old console and just wrap them in a shiny new touch screen interface. Another designer started work on it. But when I was handed back the project, I had that uncomfortable, sinking feeling in my gut. The proposed design was clunky. It was the old, clunky ATM-style interface, just drawn on a bigger screen. It worked, only to a point.

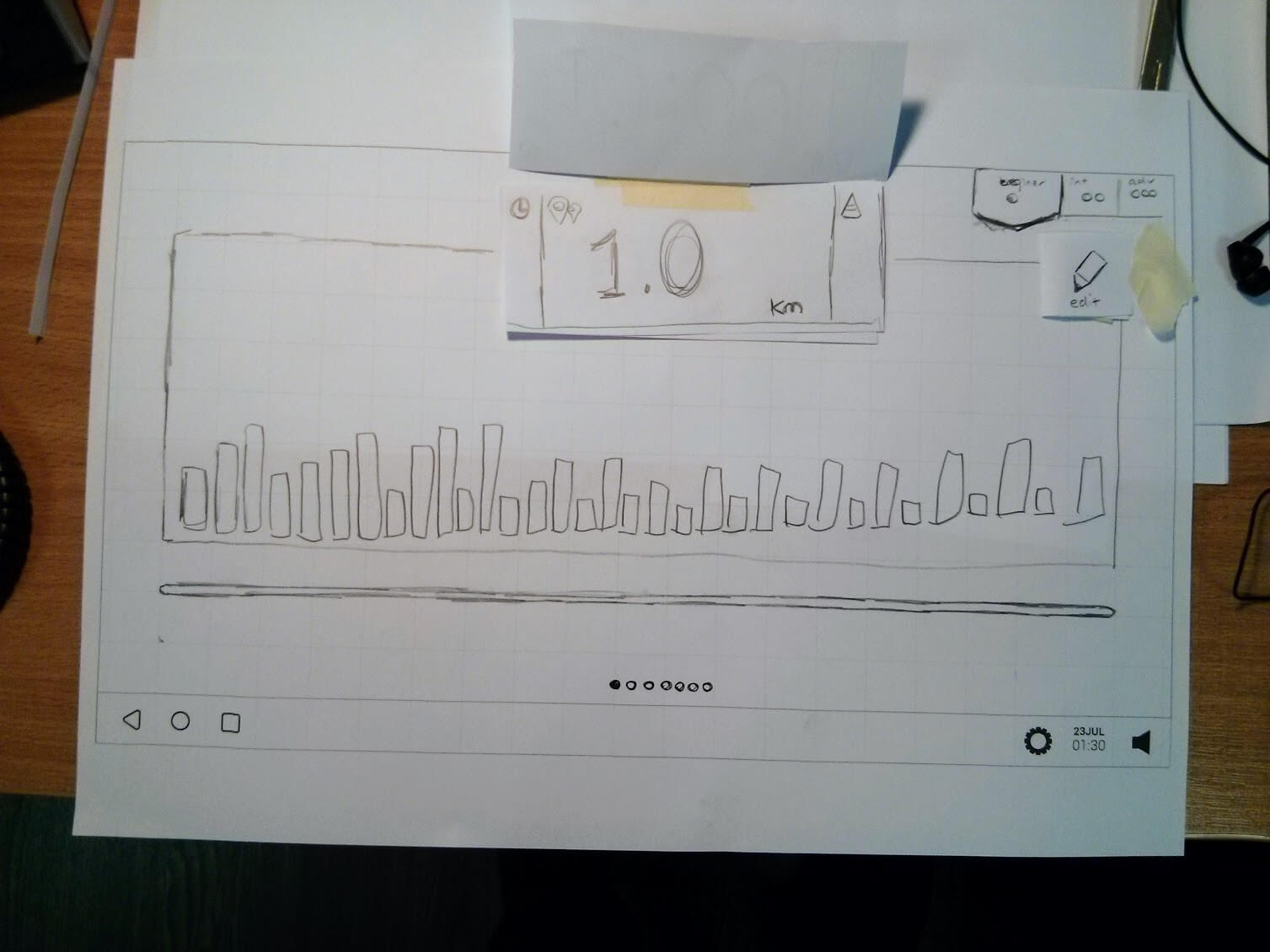

So I made the call to rework it. This was a time before Figma and Sketch were everywhere. Our weapon of choice was CorelDraw—mostly because that's what our manufacturing partners in Taiwan used. It gets a bad wrap, but I got very, very good at it. After a fair bit of paper prototyping and getting my ideas beaten up by my peers, I produced a monster of a thing: a 100-page specification document that detailed every single screen, button, and interaction. This wasn't just a design file; it was the legally binding contract our manufacturing partner would use to quote and build against.

Image: "Long before we had fancy software that could build an interactive prototype with a click of a button, this is how we had to do it. With a pen, a bit of paper, and a roll of masking tape. This was the original paper prototype for the console interface. You can see the little paper flaps I made so I could flip between the different modes to explain the concept. It's crude, it's a bit mad, but it worked. It was the first, vital step in turning a vague idea into something real."

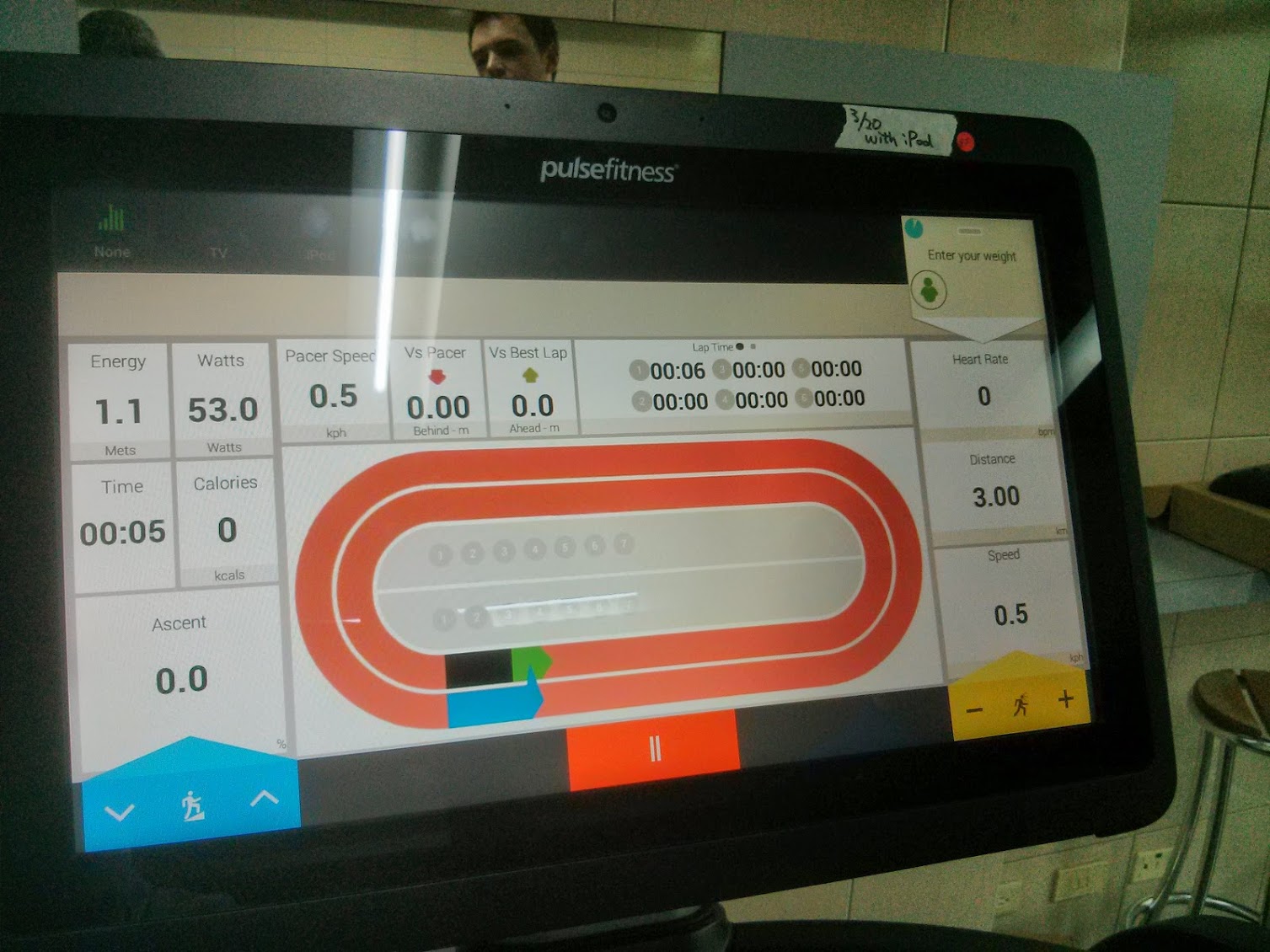

Image: At university, we used to create these product renderings with leaky marker pens. Now, of course, it's all done on computers, which means you can get it looking just right.

And what you're looking at here is the 'Pacer' mode. It's a powerfully simple idea: you tell the machine how fast you want your digital nemesis to run, and then you simply have to try and keep up. It's the most basic form of motivation there is: a ghost you have to beat.

If you look closely, you can tell this is a very early rendering, a ghost of the machine before the hardware had even been decided upon. Notice the massive, prominent NFC zone in the chin; we knew that 'the tap' was going to be the heart of the whole system, so it was front and centre from day one. And the bottom bar in the UI? Purely business for now, just the workout controls. We hadn't even got to the point of adding Netflix to distract you from the pain yet. That would come later

A long way to go for a meeting

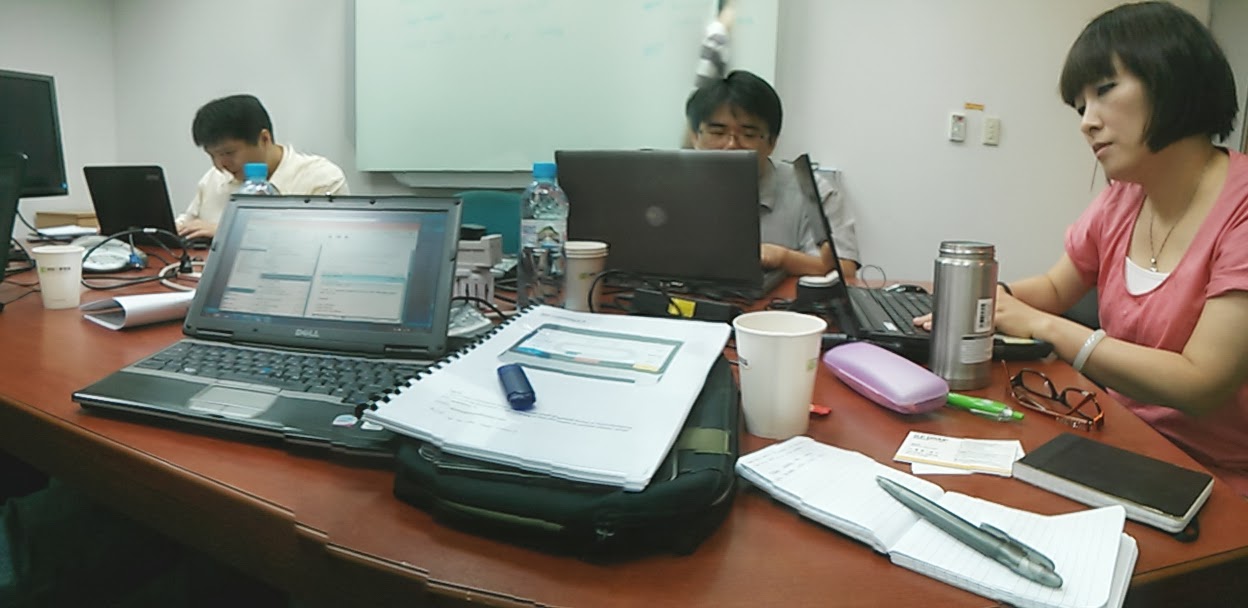

And after all that work... the prototypes, the renderings, the endless internal debates... it all comes down to this. Once the initial design was ready and the commercial deal was signed, I had to fly to Taiwan with my monster document for the handover.

This wasn't a creative kick-off; this was the moment you hand your baby over to the people with the factories. The job was to sit with their engineering team and go through the spec, page by painful page, so the thing they quoted against was the thing we actually ended up building.

Image: "This is what the start of a multi-million-pound manufacturing deal actually looks like: a borrowed laptop, a very thick spec document, and a pen I got for free from a competitor's trade stand. That printed and bound bible in front of me isn't a first draft; it's Issue 25 of the product specification, representing thousands of hours of design and refinement. No pressure, then."

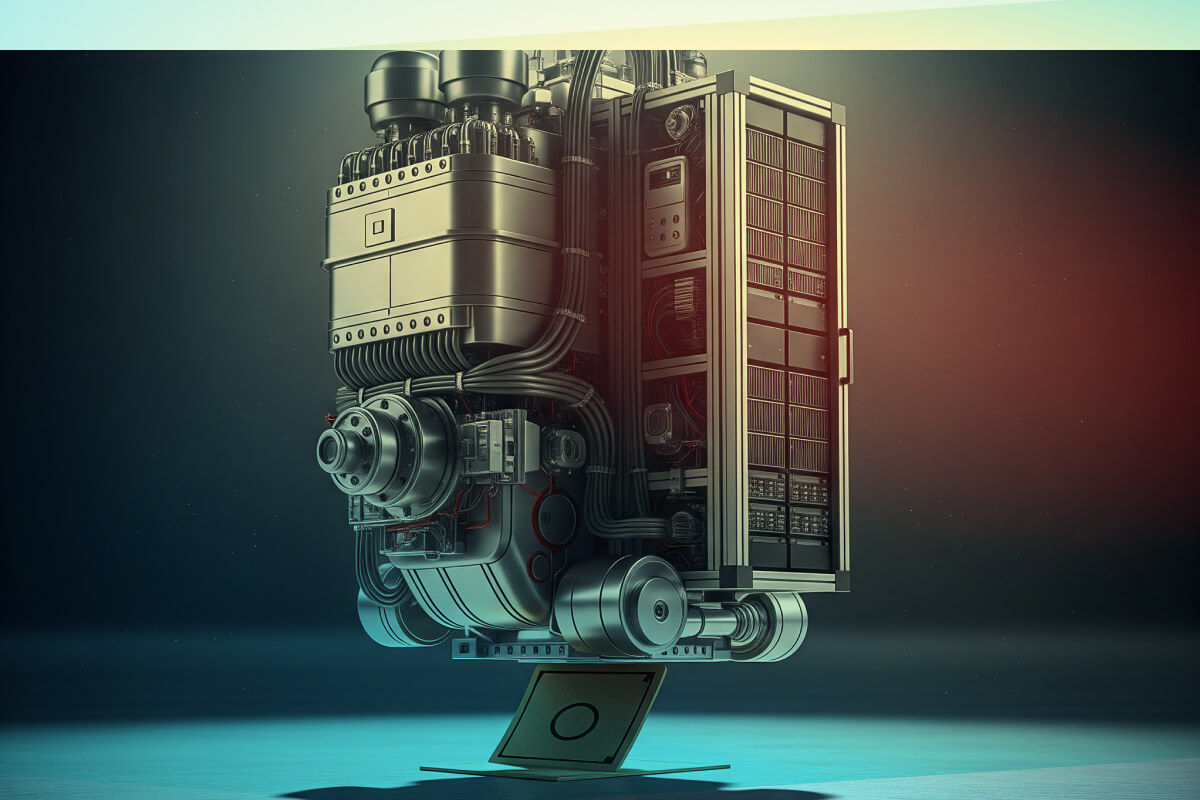

But the real genius wasn't just in the document; it was in the architecture we'd defined. Our lead engineer, a proper genius called Tony, had come up with a fiendishly clever solution. The shiny new Android board was just the "head." The real "Pulse brain" was a separate I/O board he designed, which still ran all the legacy fitness programmes and did the actual, difficult job of talking to the treadmill.

What this meant, in simple terms, was that we could plug different heads onto the same brain. It made future upgrades massively cheaper and easier. It was a proper, long-term, common-sense solution. Not just a new product, but a new platform for everything that would come next.

Then came the grind. Months of it. Flashing new software onto test hardware in the studio, finding bugs, tweaking the design, and sending updated specs back to Taiwan. I think we were on revision 25 by the end. As the big launch at the FIBO trade show got terrifyingly close, Dave started to panic. So I was sent to Taiwan for a couple of months, to be the man on the ground. Working in the same time zone, directly with the engineering team every single day, my job was to review everything, make the final calls, and make absolutely sure the thing was ready for production.

Image: "This is what I love: proper, clever engineering. What you're looking at here are the brains of the operation, the gubbins inside the console. That big metal bracket on the left isn't just a lump of steel; it's a fiendishly clever bit of design that lets you get the back off to fix things without having to unbolt the whole console from the treadmill. It's a small thing, but it saves an engineer a world of pain and swearing. It’s common sense, made out of metal."

Image: "This is what really happens before a launch. You're not in a fancy design studio; you're in a lab in Taiwan. This is the evolved Pacer mode. I'd had a flash of insight and realised that just chasing a ghost down a two-mile digital road is monumentally dull. So I gave it a proper 400m track and split the run into laps. It means a user can actually see their performance over the distance, to know if they're speeding up or, more likely, slowing down as the pain kicks in.

But this isn't just about testing if an idea is rubbish. This is the most important, unglamorous part of the entire job: protecting a fragile design idea through the brutal reality of manufacturing. It’s the endless fight to make sure the thing the customer actually gets is every bit as good as the thing you promised them."

The endgame: From paper workout cards to a connected fitness ecosystem

The launch of the Android console at FIBO was a success, with even our biggest competitors crawling all over the new hardware. But the real impact wasn't just the buzz on the day; it was the culmination of a journey I had been leading for over a decade. The console was never really about the console itself. It was the keystone in a much larger architectural vision: a fully connected gym management ecosystem.

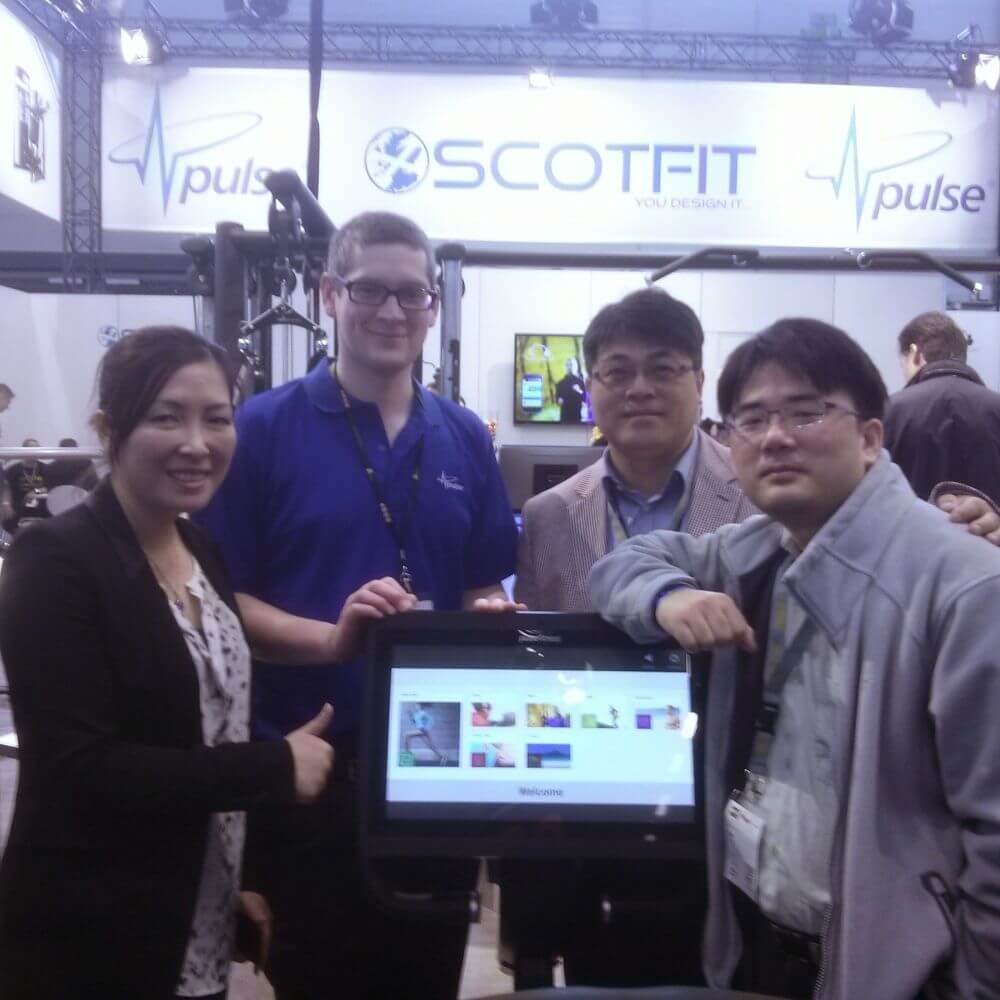

Image: "And here it is: the finished article, under the bright lights of the FIBO trade show. After all the prototypes, the flights to Taiwan, and the endless refinements, this is the moment it all becomes real. That's me in the blue company polo, alongside the key people from our manufacturing partner—their Head of Sales, the lead developer, and the project manager.

This picture is the story of the whole project: a massive, international team effort, in a frantic race against the clock to get this one, brilliant piece of kit over the finish line for the show deadline."

From paper to pixels

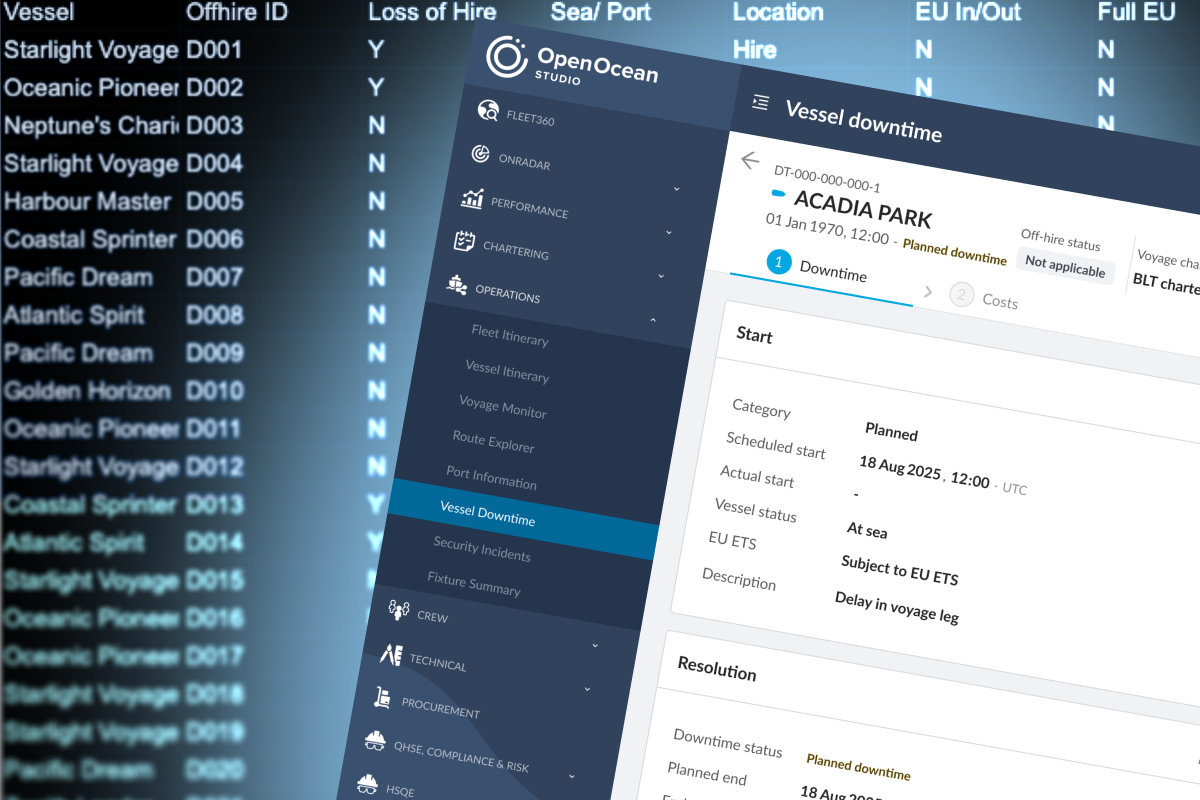

It all started in the early naughties. Gyms ran on paper workout cards pulled from a filing cabinet. A sales guy had a smart idea to digitise it, and by happy coincidence, our genius engineer, Tony, had already slipped a smartcard reader into our hardware. With no product manager and a dangerously loose brief, I was the young designer tasked with turning this idea into reality. The first MVP quickly evolved into "Smart Centre," a full-blown, on-premise gym management system I designed, with kiosks and back-office software.

From local to the cloud

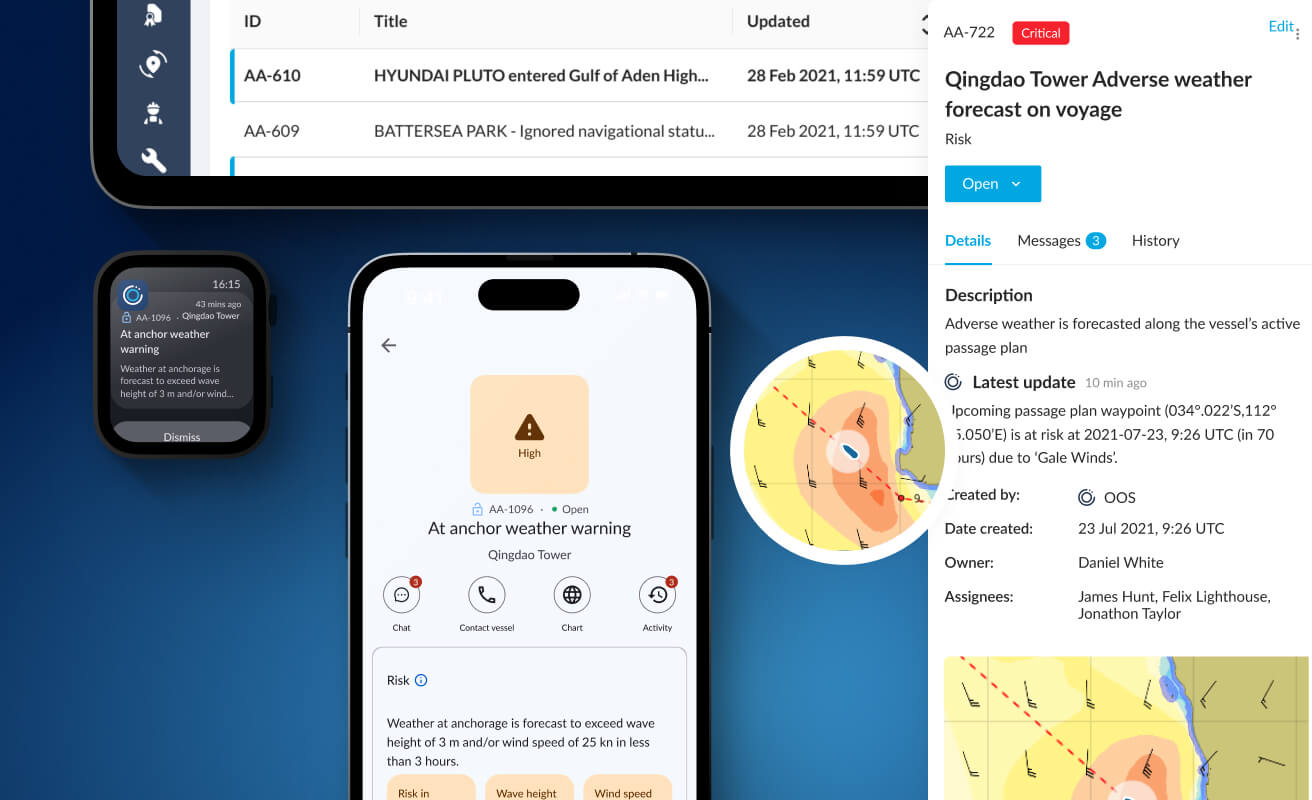

Then the iPhone arrived and changed everything. Suddenly, members wanted their workout data outside the gym. This was the catalyst for the next great leap. We had to drag the entire system from a local install into the cloud. This unlocked the ability for me to lead the design of the company's first mobile app, connecting the member to their data, wherever they were.

From cards to a tap

This cloud infrastructure is what made the new Android console truly revolutionary. It meant we could finally kill the clunky smartcard. The new console, with its integrated NFC technology, was the gateway to a seamless user journey. It allowed us to move from clunky smart cards to simple, waterproof wristbands that members could use not just to log in to the treadmill, but to open their locker and even to pass through the gym's turnstiles.

Of course, I didn't build the entire digital backbone for this ecosystem myself. To turn my designs for the console's NFC connection, the new customer website, and the mobile app into a reality, we needed a top-tier technical partner. That job fell to an agency called Carbon Digital. They were the ones in the engine room, responsible for building the complex APIs and infrastructure that made the whole thing tick.

Image: "This picture says it all, really. That's Kev, our long-suffering IT manager, stood next to the original Smart Centre kiosk. In its day, this thing was properly clever. But it was also chained to a server in a broom cupboard in the back office, which meant your workout data was essentially trapped inside the gym. It was the digital equivalent of a landline telephone in a world that was about to discover the iPhone. Its days were numbered, and we all knew it."

Video: "This is the end of fumbling for a grubby smart card. This is the simple tap that logs you in, knows who you are, and gets your workout started. Behind the scenes, there's a frantic, international conversation happening between the console team in Taipei and the API team in Surrey, but all the user sees is glorious magic.

From a console to a platform

The success of the V1 console led to the next challenge. I pushed for a faster, more capable hardware spec, which allowed us to evolve the product even further. The V2 software, which I designed, turned the console from a closed device into a proper entertainment platform, capable of running third-party apps like Netflix and games. For the first time, we also built a service login, which started to give us real, hard data on how the machines were being used. A decade of designing fancy workout programs, it turned out, was mostly ignored by the 90% of people who just wanted to press "Quickstart." A sobering, but fantastically useful, piece of information.

This is the real story. My work was to see beyond a single product and architect the entire, holistic ecosystem. The final, unfinished piece of the vision was to connect all the console data back to Smart Centre, allowing for remote software updates and centralised management. The work didn't stop with our own ecosystem. One of the biggest technical and strategic challenges was a partnership to integrate our console with eGym, a major German fitness company. This meant working across companies, across countries, and across languages to make two completely different systems talk to each other. I worked directly with their product team, led by Mikael Bourdon, to get the job done.

We didn't just give the company a new treadmill console; we dragged them, step by step, from the age of paper and filing cabinets into the modern, connected world.